Palm oil and timber industry driving increased rainforest destruction

: The destruction of tropical forests remained at alarming levels in 2018. The development was particularly dramatic in previously untouched rainforests: 3.6 million hectares of old-growth forest were cleared last year alone – an area larger than Belgium.

“The world’s forests are in the emergency room,” said Frances Seymour of the World Resources Institute: “Even though they are recovering from extensive burns suffered in recent fires, the patient is also bleeding profusely from fresh wounds.”

According to recent analyses by Global Forest Watch, the situation is especially serious for old-growth rainforests. These richly biodiverse primary forests contain trees that are hundreds or thousands of years old and provide habitat for orangutans, elephants, tigers and countless other species. At the same time, they are home to numerous indigenous peoples.

A total area of 12 million hectares of forest was destroyed in the tropics in 2018. This is the fourth-largest area lost since record-keeping began in 2001.

In terms of area, the worst offenders are Brazil (1.34 million hectares), the Democratic Republic of Congo (0.48 million hectares) and Indonesia (0.34 million hectares).

The rate of deforestation increased dramatically in other countries: In Ghana, the freshly cleared area in 2018 was around 60 percent larger than in 2017; in Ivory Coast it was 26 percent, in Papua New Guinea 22 percent, and in Angola 21 percent larger.

In Indonesia, the situation had improved in the wake of the devastating fires of 2015 and 2016. Experts see this as a success of President Joko Widodo’s policies, as forest destruction in protected areas declined more than elsewhere. At the same time, they fear a renewed rise if 2019 is a dry year, leading to an increase in fires. In the province of Riau, 1,000 hectares of forest have already burned this year.

In Brazil, scientists are concerned that deforestation hotspots are encroaching on the land of indigenous and uncontacted peoples whose way of life depends on intact forests. Environmentalists fear that deforestation will skyrocket under Brazil’s new president, Jair Bolsonaro – an increase was already apparent during the election campaign.

In the remainder of South America, forests face a variety of threats. Since the end of the civil war in Colombia, farmers have been settling in forest areas previously controlled by the FARC rebels. In Bolivia, large-scale farming and cattle grazing are driving the destruction of forests. In Peru, the main causes are coca farming and other smallholder agriculture, logging and illegal mining.

Deforestation is accelerating rapidly in Ghana and Ivory Coast at +60 percent and +26 percent, respectively. Cocoa cultivation is playing the decisive role there, with much of it encroaching on national parks and other protected areas.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, deforestation was up 38 percent compared to 2017. Three quarters of those losses are driven by small-scale farming and firewood collection.

Madagascar lost around two percent of its primary forest in 2018 alone – more than any other tropical country in percentage of total forest area. In addition to smallholder agriculture, the causes included illegal sapphire and nickel mining.

Even positive developments in some regions mean that the continued destruction of forests will at best be slowed, while the cascade of negative impacts continues: “For every area of forest loss there’s likely a species one inch closer to extinction. And for every area of forest loss there’s likely a family that has lost access to an important part of their daily income from hunting, gathering, and fishing. Such loses pose an existential threat to the cultures of indigenous peoples. And for every area of forest loss there’s likely a community downstream that has less access to clean water and is more exposed to floods and landslides,” Seymour noted.

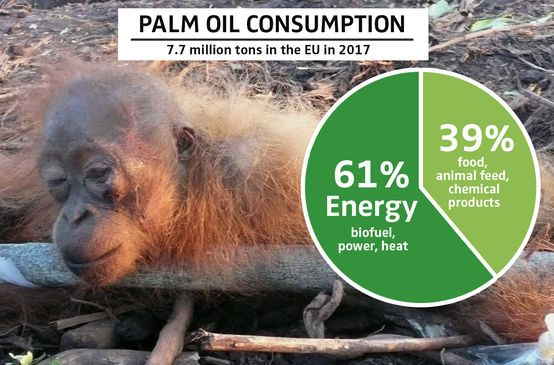

Stop rainforest destruction for biofuels!

The production of palm oil-based biofuels is destroying rainforests and the livelihoods of smallholders. NOW is the time to ban biofuels once and for all.

Support the fight of indigenous people against the palm oil industry

The indigenous Shipibo in the Peruvian Amazon are fighting to defend their rainforest against palm oil companies. Please help cover the Shipibo’s legal costs.

The rainforest

A green sea of ferns, mosses, vines and ancient trees. Iridescent butterflies and colorful birds. Flowers in every hue of the rainbow. The “green lung” is a natural wonder of the world. Find out more about the world’s most diverse, fascinating and threatened ecosystem.