UN: extinction crisis endangers us all

The current extinction crisis is a major threat to the future of humanity. One million species could soon vanish unless we take drastic action – ‘business as usual’ is no longer an option.

The current UN report on biodiversity paints a dramatic picture: One million animal and plant species could face extinction in the coming decades. The current rate of extinction is tens to hundreds of times greater than the average of the past ten million years.

Some key figures: the biomass of wild mammals has decreased by 82 percent, the area of natural ecosystems by half, and that of wetlands by no less than 85 percent. Around 75 percent of the terrestrial environment has been “severely altered” by human actions.

The situation is especially serious for tropical rainforests: between 1980 and 2000, around 100 million hectares were cleared for livestock grazing in South America and palm oil plantations in Southeast Asia, and a further 32 million hectares were lost between 2010 and 2015.

The scientists who prepared the report were themselves shocked by the magnitude of destruction. “We are eroding the very foundations of our economies, livelihoods, food security, health and quality of life worldwide,” says Sir Robert Watson, Chair of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). “We have lost time. We must act now.”

The main drivers of destruction are fishing, forestry and agriculture, in particular industrial monocultures and meat production. Population growth, rising resource consumption, pollution and the spread of invasive species are also having an impact. Climate change could cause the extinction of five percent of all species, even if we were to succeed in limiting global warming to 2°C: The habitat of most species is already shrinking dramatically and coral reefs could die off almost entirely.

The authors of the study are calling for immediate action: “People shouldn’t panic, but they should begin drastic change. Business as usual with small adjustments won’t be enough,” warns Professor Josef Settele of the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research in Leipzig, Germany.

The report also highlights the role of indigenous people living in rainforests and elsewhere as the stewards of nature.

The protection of biodiversity has finally made it onto the agenda of the G7, the seven largest industrial nations. The international community now has around one and a half years to show that it is taking the warnings seriously: in October 2020, a new UN Framework Convention on Biological Diversity is to be adopted at the Conference of the Parties (COP 15) in Kunming, China.

There is no denying it any more: decisive action to protect biodiversity is way overdue.

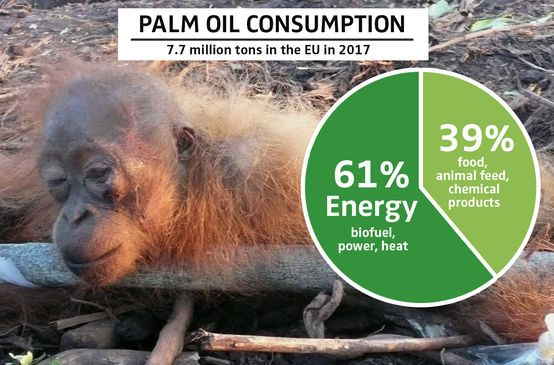

Stop rainforest destruction for biofuels!

The production of palm oil-based biofuels is destroying rainforests and the livelihoods of smallholders. NOW is the time to ban biofuels once and for all.

Borneo: orangutan rescuers need our support

Help support the heroic efforts of International Animal Rescue (IAR) veterinarians in rescuing orangutans threatened by fire and illegal logging.

Biodiversity

Life on Earth originated around 4 billion years ago. Since then, an unfathomable number of species have evolved, around half of which are insects. Numerous plant and animal species have yet to be documented, and many new ones are being discovered every day.